Isabella Lilias Trotter (1853–1928) was a gifted artist and Protestant missionary to Algeria during the Victorian Era. Born into a privileged, intellectual British family, she showed skill as an artist early in life. She also had a naturally sympathetic and nurturing soul toward those in need. The death of her father at the age of 12 would prove to be a life-altering event for her, during which she turned deeply toward prayer. In her early twenties, art critic John Ruskin encouraged her budding talent and championed her work. Although drawn toward the pursuit of a life in art, her devotion to serving God led her to surrender an artistic life of privilege and leisure. In 1888, reminiscent of Joan of Arc, Lilias claimed to be called on by God to engage in missionary work in Algeria. Facing a complex language barrier and the challenge of being a young European woman ministering in a male-dominated Muslim country, she taught the Christian faith using her appreciation of literature and artistic gift.

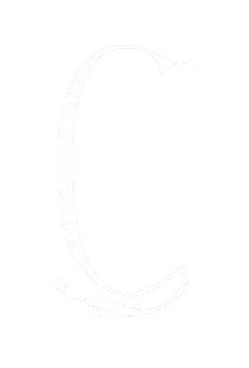

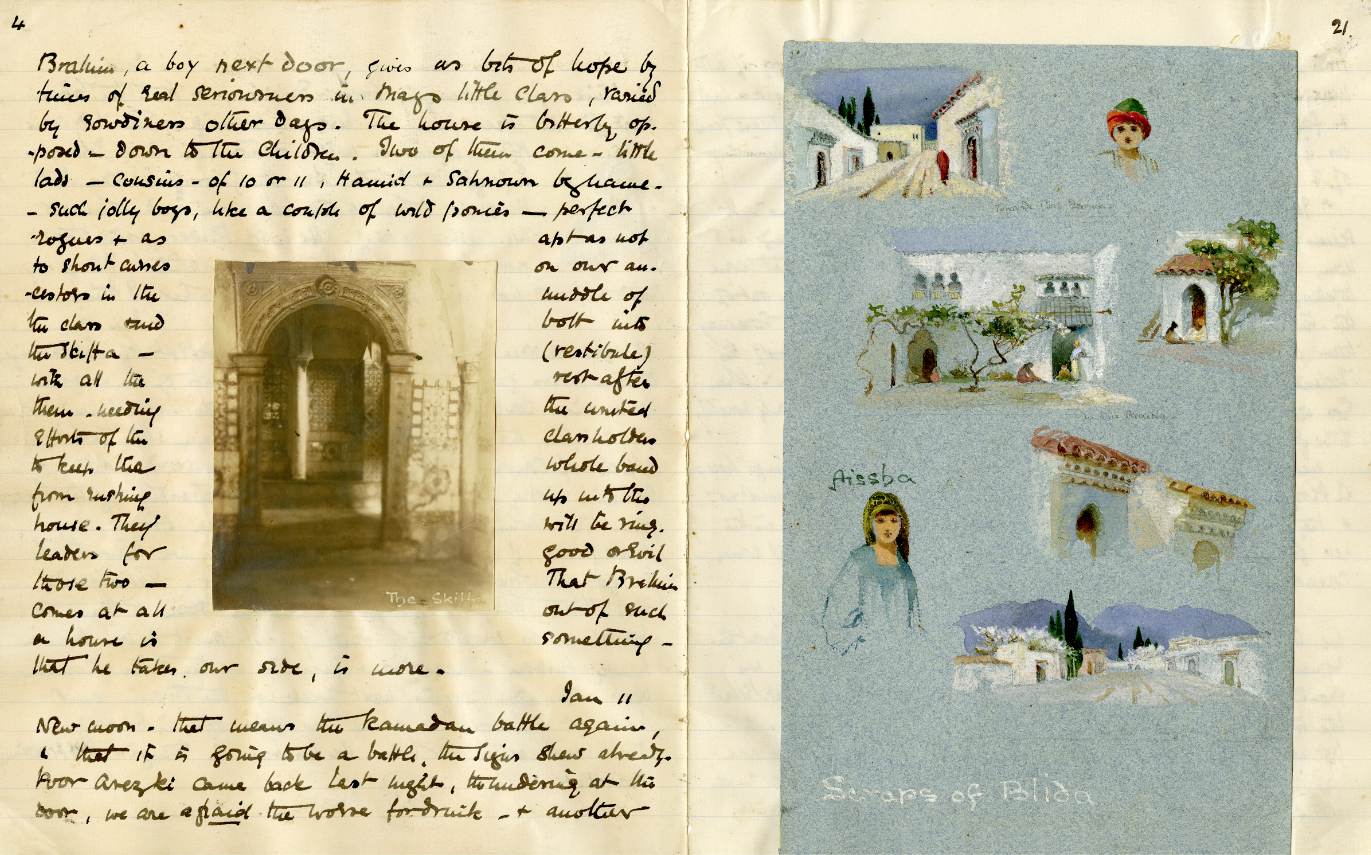

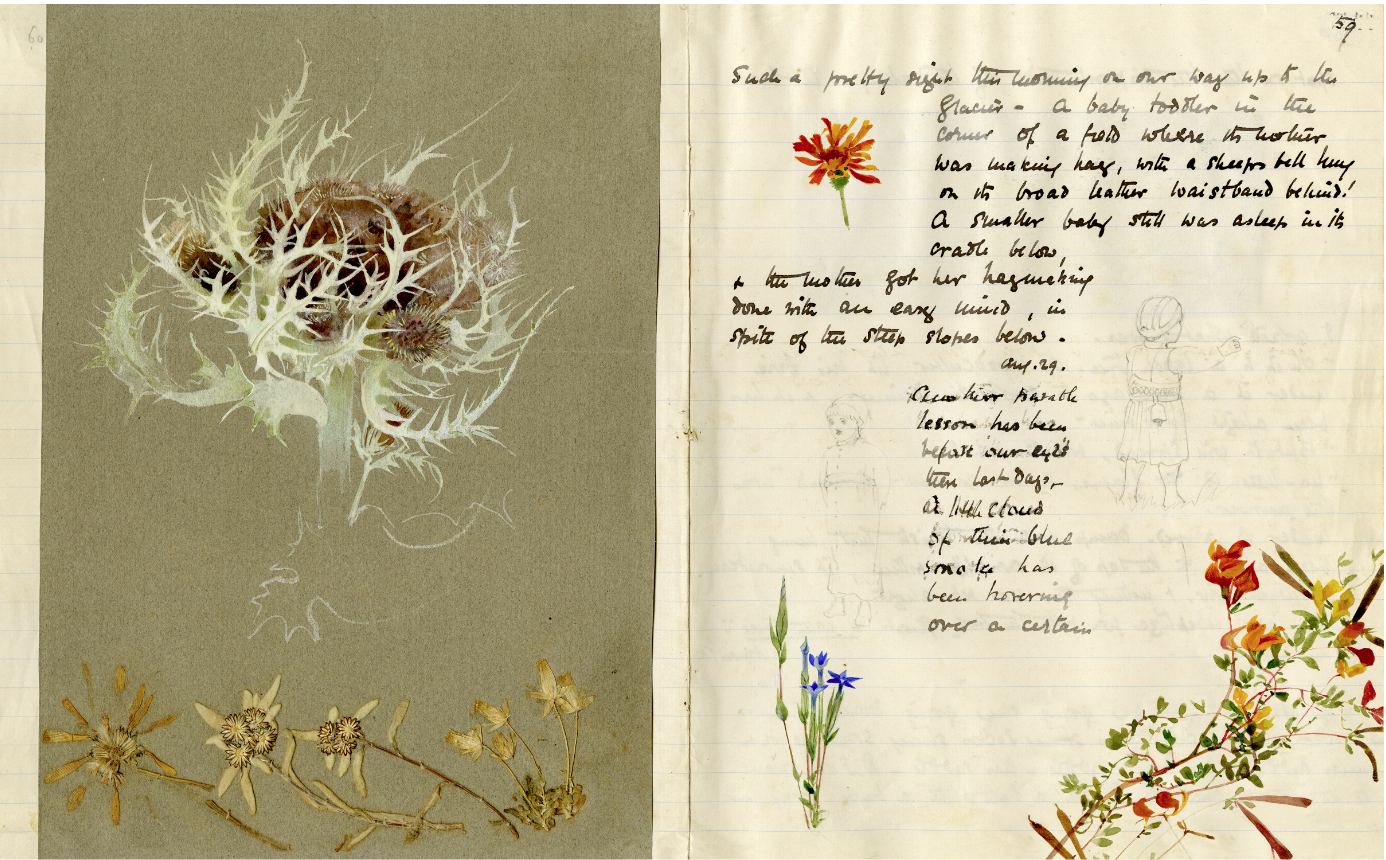

Throughout the last 40 years of her life in North Africa, Lilias documented her days in journal entries and illustrated impressions of the desert in sketches and watercolors.

Five Lilias Trotter journals (and a total of 524 pages) were discovered in England recently by private collectors Brian and Sally Oxley. They were brought to The Center for conservation, digital archiving, and reproduction. Some of the journals were sketch books, i.e.: of daily life in Venice, others were written accounts of her experience in Algeria alongside pencil and watercolor sketches of daily life there, as well as photographs. Laura Berenger, Conservator of Rare Books, and Robin Hann, Photographer and Archivist, joined forces for this project.

“One of my first thoughts in paging through the Lilias Trotter journals was, ‘These may be the most exquisite pieces I have the chance to work on,’ Laura recalled. “The Islamic inspired leather covers with simple geometric blind tooling protecting the words, photos, and paintings of such a gifted woman were unlike anything I had seen first-hand before. Travels and work that, to me, seem beyond daring are married with the most intimate and refined artwork—paintings that are spontaneous, contemplative, delicate, and majestic. These are the kinds of books that leave me in a state of awe that my hand is touching the same page as the hand that created the masterpieces.”

In conserving and treating the pieces, it was the aim of Laura and the client to stay as true to the originals as possible. Wheat paste and Asian tissue were used to repair tears and losses to the pages. Each section of the book was reinforced at the fold so that the sewing of the book did not put stress on the pages. A few pages were added to the front and back of the original pages to minimize acidic migration from the leather to the journal pages.

“The journals were in incredible condition considering their age. Having the opportunity to help them reach their original glory was a privilege,” Laura said.

For the reproduction journals, care was taken to re-create the look and feel of the original leather and blind tooling. Due to the fragility of the journals, Robin meticulously scanned each page to ensure all the wonderful details of Lilias Trotter’s pencil and brushwork would shine through. The scans were then digitally retouched to repair all the edges of each page (because of age there had been some deterioration and small pieces were missing) so that when sent to the bookbinder, Laura, they could be trimmed to the exact edge. They were then organized in layouts that would maintain their original page order but facilitate the bookbinding process. Finally, they were printed on high quality archival double-sided paper, where much care was taken to maintain the original color and texture of the journals, so that they felt authentic.

Miriam Rockness, author of A Passion for the Impossible: The Life of Lilias Trotter, recounts how these lost journals were discovered:

“I will never forget when I first set my eyes on the sketchbooks and journals of Lilias Trotter, at the home of her grand-nephew, Robert Egerton in Surrey, England. It was the end of a pilgrimage for me to locate her family and see their collection of her work—journals from the 1890's in which she recorded, in words and watercolors, views and impressions of North Africa— the land and people she had come to love and with whom she spent the final 40 years of her life. Alongside those journals was a pocket sketchbook and the larger 1876 sketchbook in which she painted her journey from Lucerne to Venice where she met the famed John Ruskin who became friend and mentor and who, eventually, brought to a head the decision which would determine the role of art in her life.

I marveled, as I examined the exquisite paintings and strong sketches—museums in miniature— how these works had survived their journey from travels on horse-pulled diligence over plateaus, donkeys over mountain passes, camels into the south-lands of the Sahara Desert. And this was just the start! Back “home” in Algiers, Lilias would send these journals to England, where round-robin-style, they were circulated amongst countless people, finally winding their way to Oxford and, with the sketchbooks, to the care of her sister, Margaret Egerton. Here they were stored in bags and boxes until decades later when the family and the archives were tracked through calling all the Egerton's in the Oxford phone book! But I couldn't help but wonder: What would become of these priceless works? Would they be returned to the storage and obscurity? Worse yet, would they be lost or inadvertently destroyed?

Fast forward almost a decade-and-a-half to 2013. Enter Brian and Sally Oxley who had become acquainted with Lilias Trotter through her biography, A Passion for the Impossible, and a compilation of her words and watercolors, A Blossom in the Desert. They sought me, her biographer, to present their vision of making a documentary film about her life accompanied with an art exhibit. Their disappointment that the bulk of her art was being prepared for deposit at the University of London was offset by learning about the Egerton collection. But there was bad news: My repeated and futile attempts to make recent contact with the family led to the discovery of Robert Egerton's death a year previous.

This was just the challenge that prompted the Oxley's to board a plane to London, hire a taxi to Godstone in Surrey, locate the home (under reconstruction) and find a source who led them back to London and to Alex Egerton, the son of Robert. He feared that the archives had been sold in unidentified auction lots but was willing to allow Brian to search the library in which the remaining belongings were gathered and being sorted for the final closing of the house. The search was rewarded by the discovery of two journals, secured in bubble wrap, stored in a shallow box on a high shelf. Several months later, the remaining journal, pocket sketchbook, and the larger Venice sketchbook (!) was found in a potato sack in the attic, having survived rats and leaks!

The rest is history. Brian acquired the archives, partnering with the family in the common goal to preserve, protect and present this priceless material for generations to come—an incentive furthered by a collaboration with The Conservation Center to conserve and make facsimile editions for wider access. Now, when I hold in my hands the reproduced journals and sketchbooks, it is hard to believe that these are not the originals: flowers and landscapes and people painted in headings and margins of the lined notebook pages; larger scenes of skyscapes and landscapes painted and pasted into the journal pages. And it is wonderful to know that many others will now encounter the same thrill that I experienced upon my first sighting of the original works!”

“We have enjoyed working with Heather and April at The Conservation Center,” said Brian and Sally Oxley. “We are impressed with the professionalism and attention to detail that we found there. Their sensitivity to and knowledge of the arts adds to the beauty of this whole process.”

Two of the Lilias Trotter journals are currently in the Wheaton College Special Collection and will soon be made available for public viewing, and another is with the Oxley’s private collection. A documentary about Trotter’s life and art is currently being produced by the Academy Award-winning Image Bearer Pictures, tentatively scheduled for a Fall 2014 release. We’ll keep you updated on the continuing legacy of these gorgeous, intimate journals.